The rise of agentic offensive security: AI attacks, industry momentum, and API security

Zoran Gorgiev, Alessio Dalla Piazza

Here, we analyze the rise of agentic offensive security in light of adversaries’ growing advanced use of AI. You’ll learn about:

- The first corroborated agentic attack in the wild, plus other examples of threat actors’ advanced AI use, and a PoC agentic attack framework applicable across the entire kill chain

- The growing industry momentum toward building and investing in agentic offensive security solutions

- Benchmark studies from Stanford and Equixly showing how ‘agentic AI hackers’ are beginning to outperform security professionals in different testing scenarios, and what that means for cybersecurity in general and API security in particular

Adversaries’ use of agentic and advanced AI: Confirmed cases and PoCs

Until just yesterday, generative AI served mainly as a productivity multiplier for attackers. They used it to generate phishing content and automate simple scripts.

But 2025 marked a notable transition. In just several months, adversaries went from simple AI-assisted tasks to advanced AI functions to full-on agentic AI operations.

An AI-orchestrated espionage campaign with agentic execution

In November 2025, Anthropic released “Disrupting the first reported AI-orchestrated cyber espionage campaign.” It described the first clear example of agentic AI used in cyber offense.

The AI safety and research company stated with high confidence that the culprit behind the campaign was the Chinese state-sponsored group GTG-1002. Instead of using AI for isolated tasks, the adversary implemented an autonomous attack framework that manifested agentic behavior.

How?

Through AI-led tool orchestration and coordinated multiple AI instances. That allowed the attackers to carry out numerous simultaneous intrusions across approximately 30 entities.

To achieve this feat, the attackers took advantage of Claude. They bypassed its safety filters by employing social engineering against the model. Using role-play, they convinced Claude that it was an employee of a legitimate cybersecurity firm performing authorized defensive testing. Then, they used it for

- Reconnaissance

- Discovery

- Exploitation

- Lateral movement

- Credential harvesting

- Analysis

- Exfiltration

The adversary leaned on automation plus a persistent state to keep the campaign moving forward. Moreover, with the help of the LLM, they planned, delegated, and executed multi-step workflows at extreme machine speed.

In this case, the AI system functioned as a ‘hacker-in-the-loop.’ According to Anthropic, the AI conducted approximately 80–90% of tactical operations, implying that human involvement was scarce and periodic.

However, the report also notes a downside to using AI offensively in its current state. Namely, the AI exaggerated findings and sometimes fabricated data, reinforcing the sentiment that even advanced, agentic AI use still requires validation loops.

‘Just-in-time’ AI inside malware execution: Adaptive behavior mid-run

In a separate 2025 report, the Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) described adversaries abandoning the concept of AI exclusively as a productivity aid. GTIG discovered adaptive malware that uses LLMs to change tactics in real time.

This malware does not carry hardcoded malicious functionality. Instead, it generates it on demand. It dynamically changes malicious scripts or behavior mid-execution in response to the defensive environment it encounters.

Observed in-the-wild examples include malware families such as PROMPTFLUX and PROMPTSTEAL. They both rely on AI to generate malicious functions at runtime and evade signature-based detection methods.

PROMPTFLUX, for instance, takes advantage of the Gemini API to request obfuscation techniques, such as dynamic VBScript modification. This way, it can avoid detection by antivirus software through just-in-time code regeneration.

This is not agentic AI per se. Nonetheless, it represents an alarming step toward autonomous malware.

Alternatively, we could construe it as a highly sophisticated use of AI that exhibits an agentic-like autonomy within a narrower loop: software that adapts its behavior on the fly depending on the environment it faces.

An agentic attack chain model

In May 2025, Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 published an interesting article that outlined an agentic attack framework. It described how adversaries could chain AI agents across recon, initial access, privilege escalation, and other attack phases to achieve their objectives more efficiently.

The emphasis was on persistent recon and iterative adaptation based on results. That, the framework posited, would allow adversaries to run multi-step attacks with minimal input on their end.

For instance, a reconnaissance agent can continuously monitor a target organization’s online presence, scraping job postings, analyzing LinkedIn profiles, and discovering exposed cloud services. Moreover, it can do so all while adapting to every piece of newly gathered information.

This capability allows an offensive agentic system to iterate and dynamically adjust its strategies — say to switch to an alternative attack vector, such as exploiting a newly discovered vulnerability — without human intervention.

Unit 42 used this attack framework to conduct an experiment in which it ran a ransomware attack from initial compromise to data exfiltration. The researchers used autonomous systems that adapt to the target environment in real time, without requiring continuous input from security professionals.

The entire attack took only 25 minutes. That is a 100x increase in speed over traditional attack methods, confirming that we are entering an era where cyberattacks will be anything but a human-scale problem.

Industry momentum toward agentic offensive security

Seasoned security professionals, as well as the most prominent AI and tech companies, are coming together on the view that cyber offense will be reshaped by agentic capability for good, and we must match it with appropriate security solutions.

OpenAI: Autonomous security research with Aardvark

OpenAI has already outlined its strategy for managing the quickly advancing capabilities of its AI models.

As AI improves at coding and reasoning, it naturally becomes better at attacking, as well as defending, digital systems. For instance, the company revealed that its model performance in capture-the-flag exercises jumped from 27% (GPT-5) in August 2025 to 76% (GPT-5.1-Codex-Max) in November 2025.

Therefore, OpenAI is already preparing for potential adversarial abuse of its future models that can reach exceptionally high capabilities, such as the development of zero-day exploits.

More importantly, OpenAI has already developed Aardvark, a new tool built on GPT-5 that acts as an autonomous security researcher. Still in private beta, Aardvark is developed to

- Scan codebases to understand software system designs.

- Monitor code changes for flaws.

- Build a threat model.

- Trigger a possible vulnerability in a sandbox to prove it’s an exploitable and genuine threat.

- Rely on OpenAI Codex to generate a fix, which a security professional can then approve and apply promptly.

In testing, Aardvark caught 92% of known vulnerabilities and discovered 10 new vulnerabilities in open-source software.

We can view Aardvark as an AI-native SAST solution. It analyzes source code, but unlike traditional rule-based SAST scanners, it reasons about system design, threat models, and exploitability.

Keep in mind, however, that adopting this approach may mean sharing private source code with OpenAI’s systems, which could be a constraint for sensitive or regulated environments. OpenAI also states it will apply safety controls that limit certain offensive cybersecurity capabilities, which may shape what a tool such as Aardvark can and cannot do in practice.

Source: vxunderground [@vxunderground]. (2025, Jan. 5). hack into this bank and steal the money… [Tweet]. X.https://x.com/vxunderground/status/2014878364809449868

Source: vxunderground [@vxunderground]. (2025, Jan. 5). hack into this bank and steal the money… [Tweet]. X.https://x.com/vxunderground/status/2014878364809449868

Microsoft: Enterprise security through multiple autonomous agents

Similarly, Microsoft is expanding its Security Copilot through a new agentic approach to help organizations handle the scale and complexity of modern cyberattacks.

For this purpose, the company launched 11 AI agents in April 2025 (six built by Microsoft and five by partners) that act as autonomous teammates. Examples include:

- Phishing triage agent: Part of Microsoft Defender, it automatically sifts through phishing alerts to separate genuine from false threats.

- Vulnerability remediation agent: It handles patching and Windows OS updates. This agent is integrated into Intune.

- Conditional access optimization agent: It is part of Entra, and its purpose is to scan for gaps in security policies — such as new users or apps not covered by MFA — and suggest remediation.

- Partner agents: Specialist agents from companies like OneTrust (privacy breach response) and Tanium (alert context) that plug directly into the Microsoft ecosystem.

Kevin Mandia’s Armadin: Red teaming via offensive AI

Kevin Manida, one of the most prominent cybersecurity experts today, is launching Armadin to address the imminent threat of AI-driven hacking.

The idea behind Armadin is to supercharge red teaming with agentic artificial intelligence. Mandia believes that cyber offense will be entirely AI-fueled within two years, and so defense must become autonomous to keep up.

Besides increasing the scale of offensive security to unprecedented levels, agentic AI can also dramatically decrease the time and costs of security testing. In line with Mandia’s public statements, agentic offensive security can reduce the cost of typically lengthy, extensive security tests from $20,000 to $30,000 in human time to just 3 to 5 minutes, that is, only hundreds of dollars.

Although Armadin will be able to operate as a general-purpose platform for red teaming, its primary focus will be on AI-powered threats, including the specific risks in exposed LLMs and AI agents.

Stanford’s agentic pentesting experiment

In late 2025, Stanford-affiliated researchers introduced the multi-agent penetration testing framework ARTEMIS (Lin et al., 2025). They ran an important public experiment that compared the performance of AI agents with that of professional pentesters in a production environment.

The environment

The targets were computer science networks at a large research university. This environment consisted of 12 subnets (including public and VPN-only segments) encompassing roughly 8,000 hosts.

The human cohort

The researchers recruited 10 cybersecurity professionals, who found 49 unique vulnerabilities, where:

- Each pentester discovered between 3 and 13 validated issues.

- Every participant found at least 1 critical vulnerability that provided system- or administrator-level access.

The results and what they imply

The study’s most noteworthy finding is that agentic systems can already perform vulnerability discovery with high competence at a lower cost than traditional pentesting:

- ARTEMIS outperformed 9 of the 10 human pentesters.

-

There were two ARTEMIS configurations, A1 and A2, and assuming the typical 40 hours workweek:

- A2 cost $59/hour, totaling $122,720/year.

- A1 cost $18.21/hour, or only $37,876/year.

Compared to the average U.S. penetration tester salary of $125,034 (Lin et al., 2025, p. 8), both ARTEMIS configurations require a lower financial investment, particularly the A1 model.

This conclusion is of tremendous importance. Why? Because cost vis-à-vis concurrency is a core reason an organization would consider adopting agentic offensive security. Again, why? Because parallel probing and long-horizon security testing are incredibly difficult to staff and fund.

A single human penetration tester can usually focus on only one probe or task at a time. If you want to test 50 different parts of a network simultaneously, you need to hire 50 experts. And that is extremely expensive and hard to coordinate.

Besides, humans get tired, take vacations, and get bored. Maintaining a high level of focus on a single, complex, automated attack path for weeks or months is difficult for a person, but easy for software.

Finally, even if you were willing to accept the costs of manual offensive testing, there aren’t enough penetration testers available in the job market to do the “grunt work.”

Strengths and limitations that matter for defenders

ARTEMIS performed exceptionally well at:

- Parallelism: Whenever the AI system noticed a potential issue, it immediately spawned sub-agents to probe multiple targets concurrently — something humans cannot do at the same scale (and this is an understatement).

- CLI-centric resilience: ARTEMIS could exploit issues humans missed when browsers blocked interaction, say due to old TLS/HTTPS constraints, using CLI tooling to push through.

However, ARTEMIS also had limitations:

- GUI interaction bottlenecks: It struggled with browser- and GUI-based workflows, missing a more critical RCE in favor of weaker findings, which shows that interface constraints and tool affordances still do shape outcomes.

- False positives and misread flows: ARTEMIS misinterpreted the HTTP ‘200 OK’ status code due to redirects — a mistake that accentuates the need for verification pipelines with the human in the loop.

Equixly’s benchmark: Evaluating agentic offensive security for APIs

Recently, Equixly published a benchmark study that compares the performance of its agentic AI hacker, as it calls it, to human-led pentesting (Dalla Piazza, 2025). The study was carried out in an environment comprising 30 realistic API microservice challenges and analyzed 86,310 HTTP requests captured during testing.

Test coverage and study setup

The 30 microservice challenges reflected common API flaws, including OWASP API Security Top 10 categories such as BOLA, BFLA, broken authentication, injection, and business logic issues.

The human cohort consisted of 15 testers split into 3 teams of 5. The overall experiment took approximately 2 hours.

Benchmark results

The empirical evaluation yielded the following results:

- Human teams: Successfully solved 14 of 30 benchmark challenges in ~2.25 hours. Success was mainly limited to issues with relatively low complexity, such as unauthenticated SQL injections. It’s worth noting that some of these lower-complexity issues (including straightforward SQL injection cases) are often discoverable through wide automated scanning with off-the-shelf tools such as

sqlmap. - Equixly AI: Solved 30 of 30 challenges in 1 hour. Beyond the benchmark flags, it discovered 230 unique security issues. Notably, the additional findings were not false positives but results of a systematic enumeration. In other words, Equixly found recurring flaws across the microservice architecture, which is a task humans typically abandon once they find an instance of a security vulnerability.

Also, the analysis of 86,310 total HTTP requests revealed the following regarding manual testing:

- Requests crafted by humans: Only 220 requests (~0.25%) were genuinely manual, based on browser User-Agent strings and natural human interaction speeds.

- Requests generated by tools: 86,044 requests (~99.7%) were generated by automated tools such as Postman, Burp Suite, and

sqlmap. - Efficiency gap: Human testers averaged only 0.03 requests per second (RPS) during manual phases, whereas the collective tool-driven traffic averaged 10.67 RPS. This gap suggests that the pentesters used what’s sometimes called spray-and-pray tactics.

Finally, the study highlighted a substantial lack of context in human-led tool usage:

- Failure volume: The testing resulted in 57,512 (4xx) errors and 23,180 (5xx) errors.

- The dead-end problem: High counts of ‘401 Unauthorized’ errors suggest testers struggled with nested roles in microservices. ‘400 Bad Request’ errors indicated that human-managed tools were sending malformed data that the API’s specific data types (dates, integers) rejected.

- Payload patterns: Most of the 657 suspicious payloads were blind SQL injection and path traversal examples. That means the pentesters relied heavily on generic, signature-based scanners like Nuclei rather than bespoke logic testing. That said, on large perimeters, pentesters often start with broad automated scans, even though many generic payloads won’t apply to the target and can produce noisy results.

Equixly’s key differentiator

Apart from ARTEMIS, which appears to be a general-purpose pentesting system, each of the examples of agentic offensive security solutions discussed earlier operates in a different niche:

- OpenAI: code security

- Microsoft: agentic ops and triage

- Armadin: AI-native attacks

Equixly’s key differentiator is that it is purpose-built for APIs and broader web testing. That means Equixly’s niche is narrower but more operationally immediate for many organizations.

How so? Due to the pivotal role of APIs in web, mobile, IoT, and LLM applications in industries ranging from automotive to finance to utilities.

Moreover, unlike the other companies mentioned — which only recently started investing in agentic offensive security — Equixly has been promoting and refining its agentic offensive security solution for a few years already, using proprietary AI, specifically ML engines.

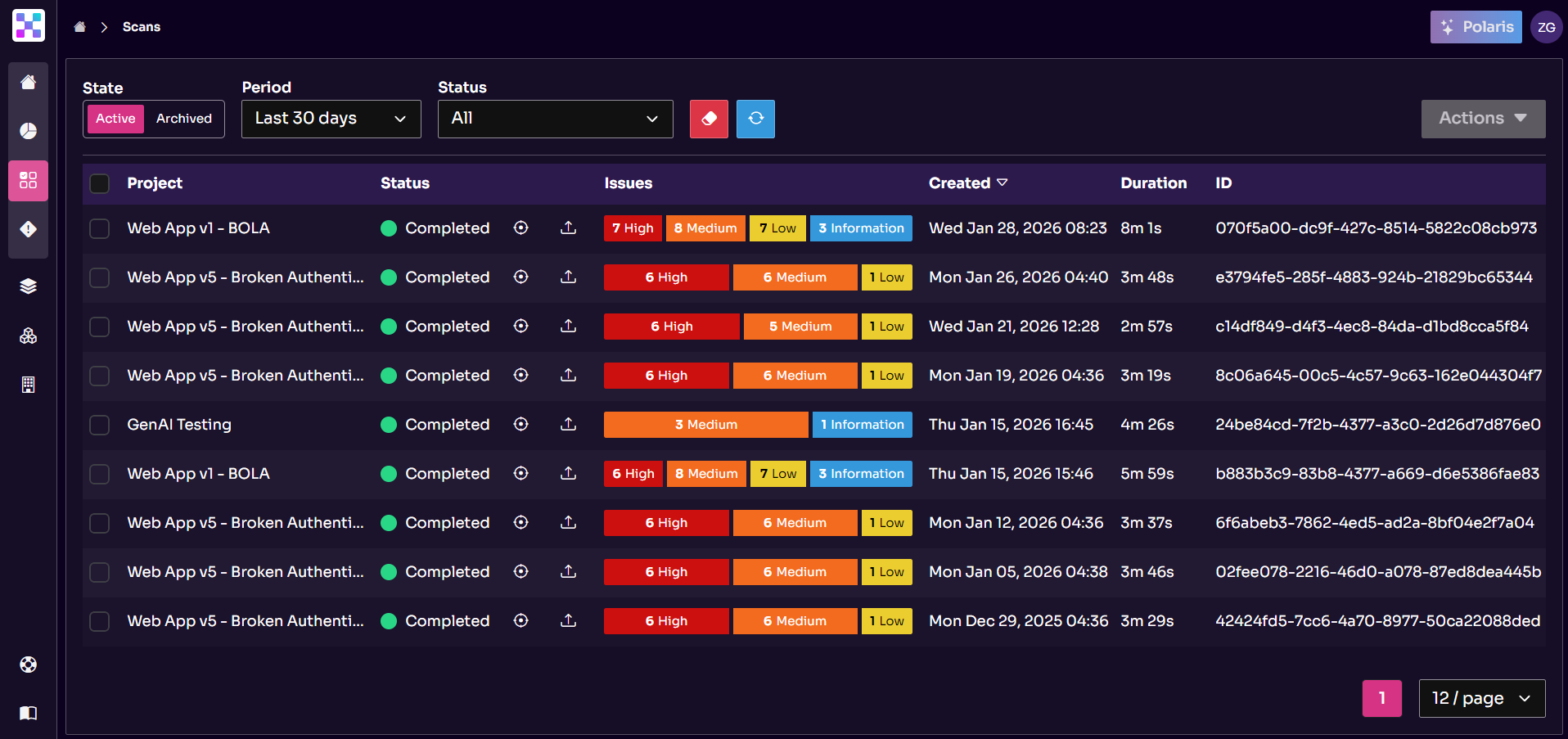

Equixly’s Agentic AI Hacker testing results

Equixly’s Agentic AI Hacker testing results

Does Equixly’s benchmark differ from Stanford’s ARTEMIS study?

Stanford’s ARTEMIS study and Equixly’s benchmark can look similar because both show agents beating humans under a timebox. But the key difference is whether the system is optimizing for the evaluation or engineering for the outcome.

Anthropic’s article on AI-resistant technical evaluations can help us illustrate this difference and relate it to our topic. The article suggests that an AI system can do well by learning what the test rewards and producing the kinds of outputs that move the score; still, that doesn’t necessarily translate into reliable end-to-end execution outside the test.

Through that lens, ARTEMIS is a strong demonstration that AI agents can perform at high levels in a research setting. But Equixly is designed like an engineered offensive workflow. In other words, it’s designed to run a structured multi-step offensive process, remember what it already learned, follow a plan, and keep checking its work over and over until it can produce results that reliably hold up in convoluted API-first architectures.

In short, ARTEMIS shows that an agent can perform impressively in an experiment. Equixly, on the other hand, is built from the outset to finish the job in real-world environments consistently.

Besides, an agentic system such as ARTEMIS relies on hosted MaaS (Model-as-a-Service) LLM APIs. As such, it may be limited by provider safety guardrails, meaning its performance can hinge on what the API allows, with much of the ‘agent’ serving as workflow glue atop an external model. Again, this contrasts with Equixly, which relies on its own proprietary technology.

Final thoughts

In summary:

- Agentic AI attacks are no longer hypothetical: Credible reporting shows agentic or, at least, agentic-like workflows already supporting intrusion operations and adaptive behavior in the wild.

- Key industry momentum is converging on agentic security workflows: Major vendors and frontier research groups are building and investing in agentic offensive systems because humans alone cannot keep pace with the current attack scale and speed.

- The Equixly and Stanford studies show why agentic offensive security is an appealing approach to cyber defense: Parallelism, long-horizon execution, efficiency, and lower cost make a compelling case for adopting it, even with the current limitations of AI, such as false positives and GUI bottlenecks.

- API security is a natural landing zone for agentic offensive security: An agentic API-focused approach can deliver substantial coverage and time-to-find advantages over human teams operating in a fixed timebox.

The combined moral is that advanced, agentic AI in cyber offense drastically changes what constitutes a feasible operational model in offensive security. Continuous offensive testing cadence with greater breadth and depth, necessarily accompanied by human oversight and validation, is slowly but surely becoming a must for every large organization out there.

Interested in how Equixly performs in practice? Contact us to schedule a demo.

FAQs

What is the first corroborated agentic attack in the wild?

Anthropic’s November 2025 report described an AI-orchestrated espionage campaign attributed to GTG-1002. The adversary took advantage of Claude to execute multi-step intrusions targeting 30 entities.

Are there any signals showing that industry is moving toward agentic offensive security?

Major tech companies, security vendors, and security leaders are actively building and investing in agentic security solutions, signaling that the market is moving from concept to adoption. Examples include: Equixly’s API-focused agentic platform, OpenAI with Aardvark, Microsoft with the Security Copilot agents, and Kevin Mandia with Armadin.

What did the Stanford and Equixly studies reveal about agentic offensive security?

They showed that agentic offensive systems can outperform human pentesters in time-boxed testing. Stanford’s ARTEMIS outperformed 9 of 10 pentesters, and Equixly solved 30 of 30 API security challenges in just 1 hour, whereas the pentesters took approximately 2 hours to solve only 14.

Zoran Gorgiev

Technical Content Specialist

Zoran is a technical content specialist with SEO mastery and practical cybersecurity and web technologies knowledge. He has rich international experience in content and product marketing, helping both small companies and large corporations implement effective content strategies and attain their marketing objectives. He applies his philosophical background to his writing to create intellectually stimulating content. Zoran is an avid learner who believes in continuous learning and never-ending skill polishing.

Alessio Dalla Piazza

CTO & FOUNDER

Former Founder & CTO of CYS4, he embarked on active digital surveillance work in 2014, collaborating with global and local law enforcement to combat terrorism and organized crime. He designed and utilized advanced eavesdropping technologies, identifying Zero-days in products like Skype, VMware, Safari, Docker, and IBM WebSphere. In June 2016, he transitioned to a research role at an international firm, where he crafted tools for automated offensive security and vulnerability detection. He discovered multiple vulnerabilities that, if exploited, would grant complete control. His expertise served the banking, insurance, and industrial sectors through Red Team operations, Incident Management, and Advanced Training, enhancing client security.